Scale Week is over, and much like the viewing audience at the conclusion of a very special episode of “Full House,” we are left to reflect on what we have learned, how we have grown from the experience, and what it all means. At the very least, it gives us a chance to end the week with this summary of six simple rules for using scales in survey research:

Scale Week is over, and much like the viewing audience at the conclusion of a very special episode of “Full House,” we are left to reflect on what we have learned, how we have grown from the experience, and what it all means. At the very least, it gives us a chance to end the week with this summary of six simple rules for using scales in survey research:

1. Keep it simple – There are many scaling techniques available to the survey researcher. Some, such as the Likert Scale are pretty straightforward, while others, such as the MaxDiff technique or Constant Sum Scaling are a bit more complicated. They all have their uses, but the researcher always needs to be mindful of keeping the survey instrument as simple as possible for the sake of the respondent. The researcher needs to use a technique that the client and those who will be reading the report will be able to understand. Some types of scaling techniques may require a great deal of prior explanation before they are administered and/or as they are being reported.

2. Stay consistent – This was already touched upon in previous posts, but it bears repeating. It is best to keep the rating system and format used in a survey consistent throughout. Don’t switch from a five-point scale to a four-point scale and then up to seven. Also, keep the positions of the value axes the same – if you start out with “least/worst/disagree/negative” type values on the left of the scale and “most/best/agree/positive” on the right, stick with that throughout the instrument.

3. Break it up – Excessive use of rating scales can be a major cause of survey respondent fatigue. This is especially true in self-administered surveys where there are long, uninterrupted lists of rating items on a page/screen or in a telephone survey where the caller must read item after item. The survey will seem much more manageable to the respondent if you break up the rating items into small chunks of perhaps three to six items at a time. If the series can be separated by other types of questions, such as simple yes/no, multiple choice, or open ends, that is ideal. At the very least, the clusters should be broken up into distinct subject headings, which brings us to…

4. Cluster related items together in a series, separate unrelated items – This piece of advice might seem like it goes without saying, but we sometimes see surveys that ignore this principle, so we will state it. Ideally, items should be placed into groups with related items. For example, if one were doing an employee satisfaction survey, some topic areas might be “Management,” “Teamwork and Cooperation,” and “Physical Working Environment.” This type of grouping will add structure and cohesion to the instrument and reduces the extent to which the respondent has to jarringly switch mental gears from topic to topic after each question.

5. Don’t ask respondents to rate more than one item at a time – This, often called a “double-barreled question,” is a common mistake among novice survey writers. Each item in a rating scale should only consist of a single concept or attribute. Consider this Likert scale item:

Courtesy might be a part of professionalism, but they aren’t the same thing. How should the respondent rate a salesperson who was extremely polite, but dressed inappropriately and gave them a tattered business card with a no-longer-functioning phone number printed on it? In this case, courtesy and professionalism should each be their own distinct item in the series. Always use one concept at a time, and always keep in mind that even if you think two words mean exactly the same thing, the respondent might not think that way.

6. Take advantage of new scaling tools…when appropriate – There are many ways to express the values on a scale rather than just words or numbers. Graphical slider scales can be a simple and intuitive way to represent the points on a scale. Consider the five- and three-point scales below that clearly convey a meaning without needing any words or numbers:

These kinds of graphic scales can be appropriate in instances where one is surveying a younger audience, or where respondents might not have a full command of the language in which the survey is written. On the other hand, they might be a little too light-hearted or cartoon-ish for a survey about, say, banking. Along with graphic representations, online surveys present different options for the scale tool itself such as an analog-looking slider, rather than traditional check boxes. The key with these new options is to always consider the audience for which the survey is intended (not to mention the general level of traditionalism of the research client!) when deciding what is appropriate.

We here in the Bunker hope you have learned everything you ever wanted to know about scales in our First Annual Scale Week. With the knowledge you now possess, feel free to express your opinion on this or any other article in the series below on…you guessed it…the starred rating scale.

- Click Here to view the Day 1 post on Constant Sum Scaling.

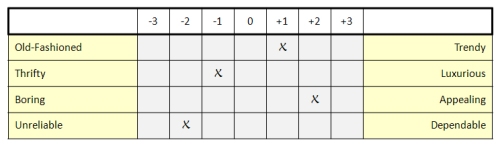

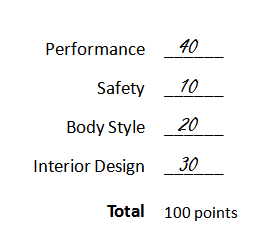

- Click Here to view the Day 2 post on Semantic Differential Scaling.

- Click Here to view the Day 3 post on Likert Scales.

- Click Here to view the Day 4 post on Scaling Mistakes | What Not to Do.